I was on a plane last weekend. Actually four planes, three different airports. Hundreds of my fellow humans on all sides.

Every one of us was scared. How do I know that? In the time of Coronavirus, we’re all scared!

For me, it’s been a low level hum. I know it’s there. I am doing my best to stop that fear from guiding my decisions and actions. But like a song that’s stuck in my head, I know it’s there.

Keep your hands away from your face.

AAGH I just scratched my nose!

Am I going to die?

For a week before this trip, I could feel it. Because Catalytic Thinking is rooted in brain science, I knew what was happening to me. I knew it when my heart felt like it would thwump out of my chest, reading about symptoms and death rates. I knew it when that thwumping turned into a full blown anxiety attack on the first of those plane rides.

Just because I knew what was happening to me didn’t mean I could stop it right then and there. Evolution has created those fear mechanisms to keep us alive. That evolution was not going to let go without a fight!

My understanding does, however, help me to see the fear for what it is, and importantly, to find a path to calm when I find myself slipping into fear’s grip.

So I wanted to share with you some of the basics of what I’ve learned, as well as some things you can do when you sense fear taking hold.

This is Your Brain on Fear

During times of crisis and extreme uncertainty, you may feel like you’re not yourself. Perhaps you’re finding it hard to concentrate. You may suddenly be dropping things, feeling unusually clumsy. You may be spending hours playing solitaire or mindlessly flipping through Instagram. You may have trouble sleeping or eating. Or maybe it’s the opposite, that all you want to do is sleep or eat (or both).

All those responses are actually built into our DNA. Here’s the science:

The primary purpose of all animals, humans included, is to survive, so that we can eventually reproduce. Survival is therefore the primary function of our brains.

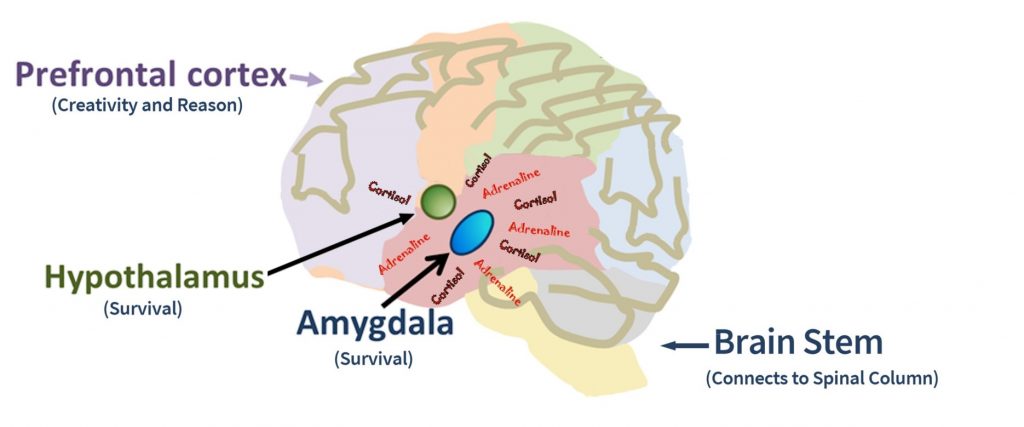

In humans, the reflexive survival areas of the brain are located at the base of the head, directly connected to the spine and the rest of the body, for immediate access to the body parts that will get us out of danger.

In addition to that survival mechanism, we humans also have a well-developed capacity for reason, creativity and compassion. That capacity for higher thought is primarily centered at the front of our heads, in the frontal lobe of the brain.

Given the brain’s primary function of survival, when we perceive a threat, the survival center reflexively triggers chemicals like adrenaline and cortisol into our bloodstream.

We all know what a rush of adrenaline feels like. Adrenaline is one of several hormones that increase our heart rate and blood pressure to get us moving quickly.

To clear the way for those get-moving chemicals to do their job, chemicals like cortisol slow down the bodily functions that are not necessary for survival – digestion, metabolism, the immune system. We’ve all heard that when we’re under stress, we might gain weight or have stomach problems. Cortisol and its slowing-down counterparts are actually doing that on purpose, because properly metabolizing your lunch is secondary to getting out of danger.

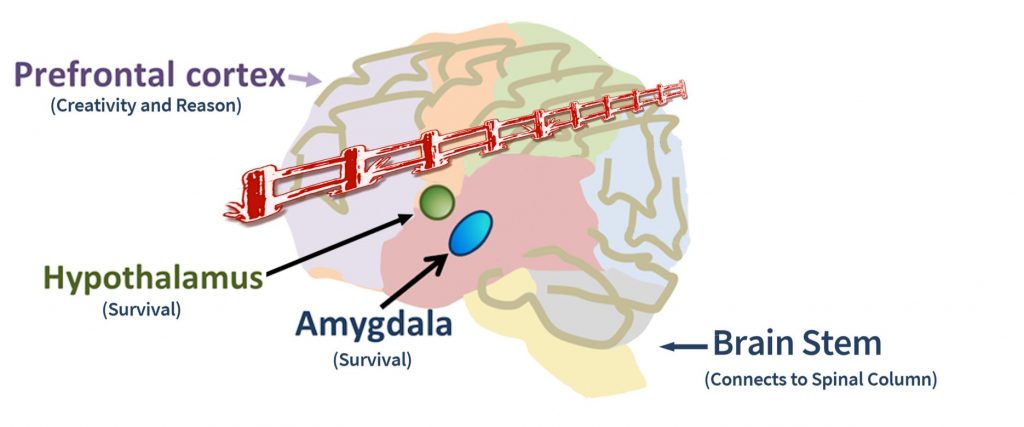

Important for this discussion, when we feel threatened, access to the thinking parts of the brain is also seen as “unnecessary,” because when we are in danger, our bodies need to just go, not think about it. So when we’re afraid, if we’re not thinking clearly, that’s not us being silly or forgetful – it is instead those chemicals like cortisol, doing their job to keep us safe, to pave the way for get-moving hormones like adrenaline to get us out of there!

Here is what makes this so important:

The survival region that is in charge of releasing those chemicals is incapable of thought. Instead, this area is a reactive, reflexive machine, ruled by and ruling our emotions, and pre-programmed from birth simply to keep us alive.

What that means for our day-to-day lives is this:

When we are afraid, a mechanism that is NOT capable of rational thought is the guard whose job is to keep us away from the area that IS capable of rational thought!

That explains why, when we perceive a threat (like the fear of Coronavirus), our brains do not know the difference between a real threat and a perceived threat. Nightmares, for example, wake us up with our hearts pounding and blood pressure sky-rocketing, even though the threat is not real. It is also why any stress – a deadline, a pile of work on our desks, money fears, and in current circumstances, fear of a potentially deadly disease – will trigger those involuntary responses. Those survival mechanisms are not weighing the facts, because they are not capable of doing so.

So first, it’s important to know that if you’re not 100% yourself these days,

that is 100% normal.

When the brain’s survival functions are ruling our actions, therefore, we humans could almost predict our reactions. We suspect other people, we hoard resources, we hunker down, we make short-sighted and often downright outrageous decisions – all instigated by an involuntary chemical response to feeling threatened.

I spent much of last weekend on airplanes that were packed to capacity with 200 strangers from all over the world. On each flight, I diligently wiped my aisle seat with disinfectant wipes, offering wipes and hand sanitizer to my seatmates.

On one of those flights, two sisters were my seatmates, and they seemed to struggle from the time they arrived. They couldn’t find their own package of wipes, grateful that I was sharing mine. Before we had even taken off, the one by the window had spilled her coffee all over the floor by her feet. An hour into the flight, the sister next to me spilled her iced tea on her tray table, missing her laptop keyboard by a fraction of an inch before we all dove in with napkins.

Still an hour from our destination, my immediate seatmate looked distraught as she rummaged once more in her purse for something else she couldn’t find. “This is so not like me,” she mumbled to herself.

All of that is what happens when our survival brain is in charge. (During this American election season, it is important to note that politicians know we cannot think clearly when we are afraid – that we are easy to manipulate when our survival brain is in charge. Beware of messages from either side that make you feel afraid!)

During this current pandemic, when we are all afraid of something very real, about which we have zero control, every single one of us has at least a low hum of that fear as our baseline.

Suddenly fighting over toilet paper in the supermarket makes sense. We are chemically, biologically being held hostage from the rational, creative parts of our brains.

Those of you who are students or practitioners of Catalytic Thinking know that the key to accessing our ability to think rationally and creatively is to create conditions that keep the survival brain calm, creating feelings of safety. That wisdom guides the Catalytic Thinking framework, because when we are not afraid, we humans have boundless potential for good.

What leads to our feeling safe?

There are many conditions that help us to feel safe. Let’s consider just a few of them.

Connection

The keys to our survival do not solely rely on our ability to fight, flee or freeze. Because we humans are not stronger or faster than animals who might consider us food, our survival also relies upon each other, just as it is with other pack animals.

Not surprisingly, therefore, neuroscientists have found that our ability to connect with each other, feeling what others are feeling, is also hard-wired into several reflexive functions in the human brain. If you have ever watched someone touch a hot stovetop, and reflexively grabbed your own hand as if that victim were you, you have experienced the brain’s instant empathy mechanisms.

Simply put, we need each other. Our brains therefore do not only make connection possible, but necessary. Infants deprived of direct human contact fail to thrive, and may even die. Similarly, a hug can soothe anxiety because feeling a nurturing touch releases oxytocin, one of the many feel-good chemicals that help us do what is good for us.

For her whole adult life, my mother’s blood pressure would spike when she went to the doctor. While she was normally extremely healthy, the doctor had no choice but to put her on blood pressure medicine, simply because her BP would be so very high when he saw her.

One day a new doctor was standing in for her regular physician. As he took her blood pressure, he cradled her arm in his, slowly and gently massaging that arm as the cuff squeezed around her. For the first time ever, her BP was completely normal. After that, whenever I accompanied my mom to the doctor, I held her hand while they took her blood pressure. That simple act got mom off those meds for good, simply by adding “touch” into the equation.

Seeing the path

Humans are highly visual creatures. Our fear of the dark is directly related to our fear of being unable to see. When we cannot envision (see) a path out of the darkness, whether that is real darkness or metaphorical darkness, that unnerves us.

We therefore feel safe when we can see a path to safety. When we can predict what will happen, using knowledge gained in the past to have a sense of control over the present, our survival brains calm down a bit. The more our highly visual brains can see what to expect without being caught by surprise, and the more we can envision a path to safety, the safer we feel.

Our Current Options

Unfortunately, we are in highly uncertain times right now. The threat of illness is very real, and the threat of economic disaster on the heels of that disease feel more and more likely as the whole world shuts down and self-isolates.

Whether we are thinking about the illness itself, or thinking about the economic reality that so many of us are already facing as the whole world economy grinds to a stop, we do not have predictability to keep our brains calm. We do not have control. We cannot see the path to safety.

What we DO still have is the ability to know what’s going on in our heads, to work with the innate ability for calm that is locked inside our brains. And importantly, we DO still have our connection to each other.

Those two functions hold the key to accessing our uniquely human capacities for reason and creativity during these unsettling times.

In Part 2 of this post, learn 8 things you can do to calm your survival brain. Click here for those tips.

I really enjoyed reading the extract in the lastest Retina NZ newsletter. Thank you for this as it really explained why we react the way we do in uncertain times.